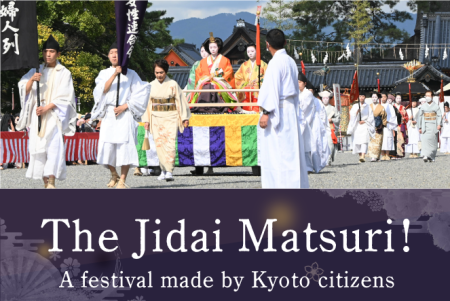

The dazzling Edo-period women’s procession

The Jidai Matsuri, one of Kyoto’s three major festivals, is held every year on October 22.

Unlike the Gion Festival, the Aoi Festival, or the Gozan no Okuribi, the festival is operated by the Heian Kosha, an organization formed by Kyoto citizens.

Among the processions, the Edo-period women’s procession, in which women wear resplendent and luxurious costumes, is the flower of the Jidai Matsuri.

In this festival made by Kyoto citizens, the group in charge of the Edo-period women’s procession is the Kyoto City Regional Women’s Federation.

In 2022, a child of an active MK Taxi driver will also appear in the role of Gyokuran, so we asked them for an interview.

What is the Jidai Matsuri

The Jidai Matsuri, begun with hopes for Kyoto’s revival

The Jidai Matsuri began in 1895.

Compared with the Gion Festival and the Aoi Festival—both of which, among Kyoto’s three great festivals, have histories of several centuries or even over a thousand years—it is a festival with a relatively short history.

The Jidai Matsuri started as an event to celebrate the 1100th anniversary of the transfer of the capital to Heian and the founding of Heian Shrine.

The 1100th-anniversary celebration of the Heian relocation was planned as a catalyst to revive the city of Kyoto, which had declined after the capital was moved to Tokyo.

That it was not held in 1894—exactly 1100 years later—was due to the impact of the First Sino-Japanese War.

At the Fourth National Industrial Exhibition, the marquee event of the 1100th Anniversary of the Transfer of the Capital to Heian, a reconstruction of the Chōdō-in from the time of the capital transfer was built on the exhibition grounds.

Using this reconstructed building as its shrine structures, Heian Shrine was founded in the same year.

Unlike ordinary shrines, Heian Shrine was established as the tutelary deity for all Kyoto citizens and as the overall guardian of Kyoto.

The first Jidai Matsuri was held on October 25, but beginning with the second it came to be held, as a rite of Heian Shrine, on October 22—the day when Emperor Kanmu moved from Nagaoka-kyō to Heian-kyō.

In other words, it is a festival held on Kyoto’s birthday.

The Jidai Matsuri Made by the Citizens of Kyoto

The Jidai Matsuri, a festival for all citizens of Kyoto, is created by the citizens themselves.

By contrast, those directly involved with the Gion Festival—also counted among Kyoto’s three great festivals—are the residents along Shijō-dōri and in the Gion district. The Aoi Festival is likewise centered on the residents of Kamigamo and Shimogamo.

Whereas these are festivals of quite limited areas even within Kyoto, the Jidai Matsuri is a festival for the entire city of Kyoto.

Heian Shrine serves as the tutelary shrine for all Kyoto citizens.

Although its history is comparatively short, this is a major feature that distinguishes the Jidai Matsuri from the Gion and Aoi Festivals.

The first Jidai Matsuri consisted of six processions: the Enryaku Civil Officials’ Attendance at Court, the Enryaku Military Officers’ March, the Fujiwara Court Nobles’ Attendance at Court, the Jōnan Yabusame (horseback archery) Procession, Lord Oda’s Entry into the Capital, and the Tokugawa Castle Envoys’ Entry into the Capital.

In 1921 the Restoration Loyalist Corps procession was added, and in 1932 the Toyokō’s Attendance at Court (Toyotomi Hideyoshi) and the Kusunoki Lord’s Entry into the Capital (Kusunoki Masashige) were added, gradually making the festival ever more resplendent.

After the wartime and postwar interruption, when the festival was revived in 1950, three new sections were added: the Edo-period Women’s Procession, the Medieval Women’s Procession, and the Heian-period Women’s Procession. In fact, it was only after the war that the women’s processions—now the very “flower” of the Jidai Festival—were incorporated into it. Thereafter, the Procession of the Restoration Patriots was added in 1966, and in 2007 the Muromachi Shogunate Administrators Procession and the Muromachi Capital Customs Procession were added, bringing us to the present.

Adding to the fifteen sections above the Shinsen Kōsha Procession (offerings guild), the Vanguard, the Shinkō Procession, the Shirakawame Flower-Offering Procession, and the Archers’ Corps, the festival now consists of twenty sections in total, with approximately 2,000 participants.

The Jidai Festival is administered by an organization called Heian Kōsha, made up of Kyoto citizens. The procession sections are conducted through the voluntary service of the Heian Kōsha’s First through Tenth Branches (which divide the city of Kyoto into ten areas), together with the Kyoto Junior Chamber, the Kyoto City Federation of Community Women’s Associations, Fukakusa Muromachi Customs Procession Preservation, the Ōhara Tourism Conservation Association, the Katsura Women’s Association (on a rotating basis with the Katsura East Women’s Association), the geisha districts (hanamachi) of Gion Kōbu and Miyagawa-chō (on a rotating basis under the Kyoto Hanamachi Federation), the Kyoto Culinary Association, the Shirakawame Customs Preservation Society, and volunteers from Kameoka City and Nantan City.

Edo-period Women’s Procession

What is the Edo-period Women’s Procession?

The Edo-period Women’s Procession is a section featuring famous women who were active in Kyoto during the Edo period.

It proceeds fourth in the parade, following the Ishin Kinno-tai Procession, the Procession of the Restoration Patriots, and the Procession of Tokugawa Shogunate Envoys to the Imperial Court.

The named figures are Kazunomiya, Rengetsu, Gyokuran, the wife of Nakamura Kuranosuke, Okaji, Yoshino Dayū, and Izumo no Okuni (seven in total).

As with the overall order of the Jidai Festival procession, the more recent the historical era, the earlier they appear.

Kazunomiya was the younger sister of Emperor Kōmei—who is also enshrined as a deity at Heian Jingū—and is known for having been given in marriage to the 14th shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi.

It was a classic political marriage aimed at kōbu gattai (the unification of court and shogunate), yet the couple’s relationship was exceptionally good. After Iemochi died young, she also played an active role as a liaison connecting the Imperial Court and the shogunate.

She is the leading figure in the Edo-period women’s procession. Attended by two nyoju (ladies-in-waiting), she is the only one to make her appearance riding on a wheeled carriage.

Ōtagaki Rengetsu was a Buddhist nun and poet of the Bakumatsu period.

She was also a ceramic artist, and pottery inscribed with her own waka poems—known as Rengetsu-yaki—was popular.

Gyokuran was a painter, poet, and calligrapher of the mid-Edo period. Her husband was the famous literati painter Ike Taiga, and the couple were active cultural figures who produced many collaborative works. They were also known as an eccentric couple, and various anecdotes about them have been passed down.

The wife of Nakamura Kuranosuke was married to one of Kyoto’s leading merchant magnates.

On one occasion, there was a competition comparing the attire of wealthy merchants’ wives and daughters; amid a lineup of flashy outfits, following advice from Kuranosuke’s friend Ogata Kōrin, she deliberately wore a plain outfit and won great praise.

She makes her appearance attended by a single koshimoto (lady-in-waiting). True to the anecdote, the koshimoto wears a striking red, flashy outfit, while Kuranosuke’s wife is dressed plainly—so at first glance the attendant looks like the main figure.

Okaji was a poet of the mid-Edo period.

Fans on which Kaji wrote waka poems and Miyazaki Yūzensai—renowned for yūzen dyeing—painted pictures enjoyed great popularity.

Her adopted daughter’s daughter was Gyokuran.

Yoshino Tayū was a high-ranking courtesan of the early Edo period.

She was immensely popular as Kyoto’s foremost celebrated beauty.

After being contested between the kampaku Konoe Nobuhiro and the wealthy merchant Haiya Shōeki, she married Shōeki.

Izumo no Okuni was the woman who began kabuki odori, the forerunner of today’s kabuki.

She staged kabuki odori at Shijō-Kawaramachi and Kitano Tenmangū, and a statue of Izumo no Okuni still stands on Shijō Bridge.

The Edo-period women’s procession was once staffed by geiko and maiko from the flower districts, but since 2000 it has been staffed by the Kyoto City Regional Women’s Federation.

The Federation is an organization established in 1948 to promote women’s independence and social participation.

Even today it carries out a wide range of activities, and as part of promoting cultural activities, it participates in the Edo-period women’s procession.

Participants in the Edo-period women’s procession are selected through women’s associations organized by school districts within Kyoto City.

To avoid overrepresentation by any ward, balance is maintained, and roles are assigned with age in mind.

For example, Kazunomiya must be in her teens, while other roles are limited to age 27 or under.

MK Taxi handles transportation

Participants in the Edo-period women’s procession assemble at Heian Jingū early in the morning.

They have their hair done and are dressed at Heian Jingū’s wedding hall, and once preparations are complete, they head to the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

It’s MK Taxi that handles this transport.

Two jumbo taxis make two round trips to help move everyone from Heian Jingū to the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

The moment they get out, numerous photographers gather, and a photo session begins in no time.

In 2022, the first round trip arrived at 11:09, and the second at 11:41.

The other attendants change into their costumes at Heian Jingū and proceed on foot to the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Interview with the Performer of “Gyokuran”

At the 2022 Jidai Matsuri, the role of Gyokuran in the Edo-period women’s procession was performed by Ms. Haruyo Noda, a resident of Kita Ward, Kyoto City.

Ms. Noda is the daughter of Mr. Mitsuharu Noda, an employee of MK Taxi working as a driver at the Fushimi Office.

After moving to the Kyoto Imperial Palace, we conducted an interview during the time before the festival began.

How she came to take on the role of Gyokuran

“My grandmother was an officer in our school district’s women’s association, and the Kyoto City Regional Women’s Federation contacted us asking whether I would like to appear in the Jidai Matsuri—that was the starting point.

I had never taken part in a festival before, let alone the Jidai Matsuri, but I wanted to try it and gladly accepted.

I was born and raised in Kyoto, and perhaps because of my father’s influence, I’ve liked history and Kyoto culture since I was a child.”

What was your friends’ reaction?

“When I told my friends I was appearing in the Jidai Matsuri, they were all surprised. The response has been huge.

Given that, they said they definitely wanted to come see it, and many of my friends are here watching today.”

About the role of Gyokuran

“Since I was going to appear as Gyokuran, I researched her in various ways.

I came to understand very well that she was a truly distinguished cultural figure who lived with a strong sense of self.

It’s by chance, but I’m very happy to be allowed to play the role of Gyokuran.

From the bottom of my heart, I hope to lead a wonderful life like Gyokuran from here on.”

Costume and hairdressing

“I’m a little worried about whether I can make it all the way to Heian Jingū walking in an unfamiliar kimono.

This hairstyle was done by dressing my own natural hair.”

“This morning we assembled at Heian Jingū at 6:00, and it took a full two hours to have my hair done from 7:00 to 9:00.

Because of the hair styling and makeup, I was surprised by the restrictions: when washing my hair the day before I was allowed to use only shampoo, and for skincare only toner.

I’ll probably never have an experience like this again.”

Feelings just before departure

“I’m truly filled with a sense of honor.

It’s a once-in-a-lifetime memory.

I’m currently a fourth-year student, and I’m set to move to Tokyo for a job starting next year.

I’m happy to be able to take on a role like this at the very end of my remaining time living in Kyoto.

I will carry out my role properly.”

About my father

“Since I was a child, he took me all over Kyoto.

Thanks to that, I grew up as a kid who loves history and loves Kyoto.

I’m nothing but grateful for the wonderful way he has raised me.”

(Added October 25) After the Jidai Matsuri, we received additional comments from Ms. Haruyo Noda.

Impressions after completing the Jidai Matsuri

“I had never experienced this kind of hairstyle before, the white makeup, or such a gorgeous kimono, so my feelings were a mix of excitement and anxiety about walking in front of a large crowd.

I was nervous from start to finish, but I’m relieved that I was able to carry out my role safely to the end.

This will undoubtedly remain one of the precious memories that will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

Reactions from friends who came to watch

“My friends who came to see the Jidai Matsuri told me, ‘Great job—you looked so beautiful.’

I was simply filled with happiness.

I also had friends who spread the word to those who couldn’t make it that I took part in the Jidai Matsuri, which warmed my heart.”

Thanks to Everyone Involved

Even before the day of the Jidai Matsuri, the participants gathered twice for meetings.

Many people attended these meetings, and I was once again reminded that the Jidai Matsuri is created through the time and efforts of many people.

I would like to express my gratitude to everyone who gave me the opportunity to take part in the Jidai Matsuri this time, and to all those involved in running the festival.

In Closing

The Jidai Matsuri, one of Kyoto’s three major festivals, is not only a festival that attracts tourists from all over the country but also a festival for all citizens of Kyoto.

MK Taxi, which is based in Kyoto, also has various ties to the event, such as being used by those involved and by participants.

For individual employees who are Kyoto citizens, it is often the case that not only they themselves but also their family members, relatives, and friends have some kind of connection to it.

In particular, in 2022, by chance an employee’s daughter was selected as a participant in the Edo-period Ladies’ Procession, serving in the role of Gyokuran.

Although its history is still only a little over one hundred years, I hope it will continue for hundreds of years to come, like its senior festivals, the Gion Matsuri and the Aoi Matsuri.

For sightseeing in Kyoto, leave it to MK’s chartered sightseeing taxi.

Your private driver is a Kyoto expert who handles both transport and guiding.

MK Media Editorial Department

The editorial department of MK Media, the owned media of MK Taxi. Our members include Kyoto Kentei “Meister” holders, automobile mechanics, editors of the in-car public relations magazine MK Newspaper, and the managers of our official social media accounts.