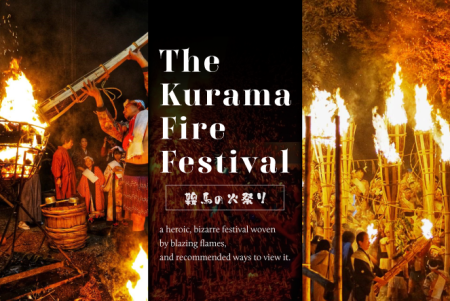

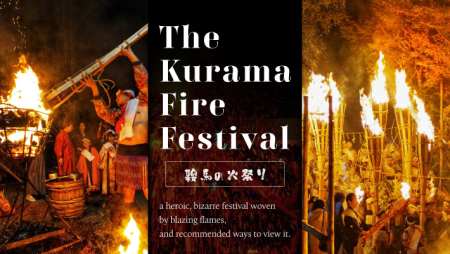

The Kurama Fire Festival: a heroic, bizarre festival

Every year on October 22, the Kurama Fire Festival is held in Kurama, Kyoto’s secluded retreat. The fervor and mystique of this stirring nighttime festival are arguably second to none among Kyoto’s many festivals.

Here we introduce an overview of the Kurama Fire Festival, where blazing flames and the men’s ardor collide. We also present recommended ways to watch the festival—something that can be quite challenging for first-time visitors.

What is the Kurama Fire Festival? — Origins and Overview —

The Kurama Fire Festival as the annual rite of Yuki Shrine

Yuki Shrine, the tutelary shrine of Kurama-dera

The Kurama Fire Festival is not the festival of the famous Kurama-dera Temple but the annual rite (reisai) of Yuki Shrine. Yuki Shrine is situated about halfway up the steep slope leading from Kurama-dera’s Niōmon gate to its Main Hall (Kondō). Until the Meiji-era separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri), Yuki Shrine was part of Kurama-dera, and the Kurama Fire Festival was conducted as Kurama-dera’s festival.

The Kurama Fire Festival Recreates Yuki Shrine’s Founding

Yuki Shrine was established when Yuki Myōjin, formerly enshrined in the Imperial Palace of Heian-kyō, was transferred to serve as Kurama-dera’s tutelary shrine in Tenkei 3 (940).

At the time of the relocation, the villagers lit torches in their hands and carried in materials while illuminating the night road. This torch procession—like a line of blazing flames—is said to be the prototype of the Kurama Fire Festival. However, the festival in its present form is only recorded from the Edo period onward.

According to one theory, lights were needed for the mikoshi (portable shrine) to be borne up and down the steep slopes late at night, and the torches used for that purpose gradually grew larger and more flamboyant, developing into the Kurama Fire Festival as it is today.

Why It’s Held on October 22

The Jidai Festival falls on October 22 to mark the capital’s move to Heian-kyō

The Kurama Fire Festival takes place on October 22—the same day as the Jidai Festival. There are plenty of hardy souls who watch the Jidai Festival during the day and then head to Kurama at night to view the Fire Festival.

By day, a procession in splendid historical costumes parades through the streets of Kyoto; in contrast, at night a heroic festival of flame is held in Kurama.

The Jidai Festival is held on October 22 because it was begun in 1895 to commemorate Emperor Kanmu’s entry into Heian-kyō from Nagaoka-kyō on October 22, Enryaku 13 (794).

The Kurama Fire Festival Formerly Held on the 9th Day of the 9th Lunar Month

Meanwhile, the Kurama Fire Festival used to be held on the 9th day of the 9th month in the old lunar calendar. This is because the transfer (enshrinement) of Yuki Myōjin took place on the night of the 9th day of the 9th month in Tenkei 3 (940).

It was around 1873 that the Kurama Fire Festival, formerly held on the 9th day of the 9th lunar month, came to be held on October 22 in the new (Gregorian) calendar. This was twenty-two years before the Jidai Matsuri began.

The details of why October 22 was fixed are unclear, but it is thought to be because the 9th day of the 9th lunar month generally corresponds, in the new calendar, to around October 22.

The Jidai Festival falls on October 22 because its old lunar-calendar date was not converted to the Gregorian calendar, whereas the Kurama Fire Festival likely falls on October 22 as a result of converting its old lunar-calendar date to the new calendar.

That the Jidai Festival and the Kurama Fire Festival are held on the same day is, therefore, a coincidence.

A Tradition Handed Down Across the Ages

Counting from the Heian period, it has been more than a thousand years; even counting only from the Edo period, when it largely assumed its present form, the Kurama Fire Festival has been safeguarded and passed down by the villagers of Kurama for several centuries.

After the war, as the livelihoods of parishioners shifted from forestry to company employment and the like, the festival was temporarily suspended in 1959, but it was revived in 1963 and continues to be held today. In reviving it, modifications were made to ease the burden—for example, rites that had continued until the following morning were changed to conclude by midnight.

Thus, although the form of the festival has changed with the times, the faith at its core and the community’s attachment to the region have remained unchanged.

For the people of Kurama, the fire festival is not merely entertainment; it is an important occasion to reaffirm their roots and deepen their bonds with the community. That is why everything—from the preparations to the operations on the day—is carried out by the villagers themselves.

The Kurama Fire Festival is a community-led event that makes a significant contribution to passing down local culture. For tourists as well, it offers a precious opportunity to experience Japan’s traditional culture.

Amid the blazing flames, feel a thousand years of history and the prayers of the people.

Highlights of the Kurama Fire Festival — Flames and the Fervor of Men

Giant torches borne by men

The Kurama Fire Festival consists of the Shinko Festival and the Kanko Festival.

The Kurama Fire Festival begins with the regular festival service at 9:00 a.m. In front of the main hall of Yuki Shrine, Shinto rites are performed, and the two deities enshrined there—Yuki Daimyojin and Hassho Daimyojin—are each transferred to their respective mikoshi (portable shrines).

The two mikoshi are then carried down from Yuki Shrine and set in place in front of the Niōmon Gate.

The basic form of the Kurama Fire Festival consists of the “Shinko Festival,” in which the mikoshi leave Yuki Shrine, make a circuit of the parish area, and proceed to the Otabisho (sacred resting place), and the “Kanko Festival,” in which they return from the Otabisho to Yuki Shrine on the following day.

In general, only the Shinko Festival, during which the torch rites are performed, is referred to as the Kurama Fire Festival.

With the “shinji-bure” announcement, the torches are lit

As evening falls, the Shinko Festival begins at 6:00 p.m.

First, in the village of Kurama, the “shinji-bure” is conducted: heralds in kariginu court robes, carrying torches, walk from the south of the village to Kurama Onsen in the north, loudly calling out, “Come to the rites!”

At the signal of the shinji-bure, beacon fires prepared at each house in Kurama—kagaribi called “eji”—are lit, and the fire festival begins in earnest. The fuel burned in these beacons is mainly red pine.

From around 6:30 p.m., to the chant of “Sairei, Sairyō,” young men bearing torches that have been lit in various places and carrying kenhoko (sword-shaped ceremonial standards) gather at Yuki Shrine’s Otabisho, while performing rites called “shorei.”

This chant is said to mean “festival, festival” and “the festival, at its best.”

First, small children carry modest torches called tokkuri torches (so named for their sake-flask shape). It begins with infants held in their parents’ arms; then progressively larger torches are borne by elementary and junior-high school students. In the end, young men walk bearing on their backs the gigantic Kaishō torch, a great torch carried by three people.

It is said to weigh over 100 kilograms at maximum, and in the days when forestry work was the main livelihood, a single person would carry it.

Each household prepares torches in various sizes—ranging from the small tokkuri torches to the large Kaishō torches—suited to the person who will carry them.

The roughly 300 torches, large and small, burned in the Kurama Fire Festival are made chiefly from brushwood of broad-leaved shrubs such as azalea, gathered from nearby mountain forests. The brush cut in June is dried on site, then collected in September and brought to the otabisho (sacred resting place).

The gathered brush is distributed to households, and the torches are made by hand. The brush is bound with wisteria vines and roots to complete each torch. There is no specialized group that makes them; the torches are handmade by the residents.

At the Kurama Fire Festival, not only the torches but also seven kenhoko (sword-shaped ceremonial standards) take part in the procession.

As in other Kyoto festivals, it is believed that the leading role in the Kurama Fire Festival was not the torches but the kenhoko. The yamahoko floats of the Gion Festival are a further development of these kenhoko.

A multitude of torches converge on the Otabisho

After 8:30 p.m., about 300 torches—starting with twelve great torches—gather at the Otabisho. The site is packed with young men, and showers of sparks rise into the air.

At the signal of the drums, the “Shimenawa-Cutting Rite,” held to welcome the mikoshi, is performed. With shouts of “O—!”, the shimenawa strung at the Otabisho is cut.

Mikoshi Descending a Steep Slope and the “Choppen no Gi”

Torches lined up on the stone steps amid flying sparks

After finishing the shimenawa-cutting at the Otabisho, the procession moves north and arrives around 9:00 p.m. at the main gate of Kurama-dera.

Once all the great torches have assembled, they are set upright on the stone steps before the gate, and the spectacle reaches a highlight as countless torches line the stairs.

The area before the gate is shrouded in heat and showers of sparks from the many torches, while a mighty chorus of “Sairei, Sairyō” rings out.

Once the great torches have fulfilled their role, they are thrown into the space before the main gate, where they burn themselves out in great flames.

When all the great torches have been thrown in, around 9:20 p.m. the Shimenawa-Cutting Rite is performed in front of the mikoshi lined up at the gate, and the mikoshi procession begins. Around 9:40 p.m., the two mikoshi—having first ascended the stone steps from the gate—descend the steep approach. An armored warrior rides on the mikoshi, and two ropes are attached to the rear; as they come down the steps, the ropes are pulled to keep them from tumbling.

These ropes are pulled by women, and pulling them is believed to bring blessings for safe childbirth. The high level of women’s participation is another distinctive feature of the Kurama Fire Festival.

“The Choppen no Gi,” in which an inverted “大” is formed on the mikoshi

At this moment, two young men grasp the tips of the mikoshi’s carrying poles, hanging in the shape of an inverted “大.” This is called the Choppen no Gi and is one form of coming-of-age rite.

Of the two mikoshi, the front one enshrines Hassho Myojin and the rear one enshrines Yuki Myojin. As stated in Yuki Shrine’s origin tale, Yuki Myojin was originally a deity enshrined at the Imperial Court. Hassho Myojin was originally the deity of Mount Kurama and used to be enshrined, separately from Yuki Shrine, at Hassho Myojinsha near the main hall of Kurama-dera.

Due to a fire in Bunka 11 (1814), it was merged into Yuki Shrine and is now co-enshrined there on a shared altar. After 10:00 p.m., when the mikoshi have come down, traffic restrictions are lifted and the congestion gradually eases.

Having descended the steep slope, the mikoshi depart the gate area around 9:50 p.m., first processing north through the parish district toward Kurama Onsen, where they take a brief rest inside.

Around 10:30 p.m. they continue south, and a little after 11:00 p.m. they make their ceremonial entry (mi-iri) at the Otabisho.

At the Otabisho, together with kagura performances, a large torch called the “kagura torch” is dedicated; it is a large torch with a distinctive shape resembling a tea whisk (chasen).

The Kurama Fire Festival concludes around midnight, when the kagura torch has burned out. On the following day, the Kanko Festival is held, in which the mikoshi return from the Otabisho to Yuki Shrine.

Recommended Ways to View the Kurama Fire Festival

A Festival Difficult for First-Timers

Few Have Seen It Even Among Kyoto Residents

Brimming with appeal though it is, the Kurama Fire Festival has one major drawback: it’s hard for beginners to view.

There are hardly any longtime Kyoto residents who have never been to the Gion Festival, and only a minority who have never been to the Jidai Matsuri or the Aoi Matsuri.

However, a great many people have never once been to the Kurama Fire Festival. That’s how difficult it actually is to go and watch in person—a key characteristic of this festival.

On the other hand, it’s fair to say that those who have seen the Kurama Fire Festival even once often find themselves going back year after year—that, too, is a notable trait.

Getting to and from Kurama Is Tough

First of all, access to Kurama is difficult. The Eizan Electric Railway is extremely crowded, and private cars are restricted from entering.

Although the Kurama Fire Festival ends after midnight, the last Eizan Electric Railway train is at 11:25 p.m., leaving no way to get back to the city from Kurama.

To make the last train, you have to cut your viewing short, and even then the trains are packed to the gills.

When, Where, and What Takes Place

Even if you’ve secured access to Kurama, the Kurama Fire Festival is still a high hurdle for first-timers.

First, you need to have a firm grasp of where things are happening and at what times.

The festival takes place throughout the entire village of Kurama along the Kurama-kaidō, but the main highlights are in front of Kurama-dera’s main gate and at the Otabisho.

The scope and specifics of traffic restrictions for visitors vary from year to year, so advance research is essential.

In the end, it all comes down to luck.

Even with that level of preparation, the Kurama Fire Festival—held in a narrow mountain valley—is subject to luck when it comes to viewing. Basically, you can’t reserve spots.

You have to follow the guidance of security personnel and organizers, and it’s not easy to be where you want at the moment you want.

If you’re lucky, you might catch the highlight scenes right before your eyes; if you’re unlucky, it’s possible to make the trip all the way to Kurama and end up going home without seeing anything.

This is a far cry from the Gion, Jidai, or Aoi festivals, where securing paid seats or staking out a spot early will let you see the highlight scenes.

Recommended: MK Travel’s “Kurama Fire Festival × Kurama Onsen” Tour

Note: As of October 14, 2025, this tour is fully booked. Waitlisting is possible. Foreign-language guides are not available.

In 2025, MK Travel will operate a special tour for the Kurama Fire Festival.

With Kurama Onsen as your base, this special tour allows for free viewing of the Kurama Fire Festival and viewing of the mikoshi procession within the grounds of Kurama Onsen—areas not open to the general public.

Of course, you can also bathe at Kurama Onsen, known as a “beautifying hot spring,” and dinner is included. After the festival ends late at night, taxi transfers to several locations within Kyoto City are also included.

By all means, please make use of MK Travel’s “Kurama Fire Festival × Kurama Onsen” tour.

Highlights of the MK Travel Tour

Taxi Transfers Included

Between Kibuneguchi and Kajika Bridge on the Kurama-kaidō, vehicles are prohibited from 3:00 p.m. on the 22nd.

On MK Travel’s special tour, after assembling at Kyoto Station (Hachijō Exit), participants split into taxis and, detouring around the closed section, take a long route from the north to Kurama Onsen.

For the return trip, after road closures are lifted at 24:00, taxis will take you to various locations within Kyoto City. While 13 drop-off points are set in advance, this is negotiable, and it may be possible to drop you at your home or lodging.

Bathing at Kurama Onsen

By the time of the Kurama Fire Festival, autumn has set in, and nights can be quite chilly.

Around 24:00 on October 22, when the festival draws to a close, temperatures in Kyoto City ordinarily fall below 20 °C; in 2005 it was as low as 10 °C.

Moreover, Kurama lies in virtually the same area as Kibune, known as Kyoto’s summer retreat, and it is typically about 5 °C cooler than the city.

The MK Travel tour includes bathing at Kurama Onsen—perfect for warming a chilled body.

The open-air baths are available until 9:00 p.m., and the indoor baths until 12:00 a.m., with unlimited entry.

It’s also ideal for washing off the soot and smoky smell after being showered with sparks from the torches.

Viewing the Mikoshi Procession from Areas Restricted to Officials

At its heart, the Kurama Fire Festival centers on the mikoshi of Yuki Shrine parading through the parish district.

On the MK Travel tour, you can view the mikoshi within the grounds of Kurama Onsen.

The two mikoshi that come from the direction of Kurama-dera take a short rest inside Kurama Onsen and then head back toward Kurama-dera.

You can view the mikoshi from close up.

Relaxing Time at Kurama Onsen

On the MK Travel tour, you use Kurama Onsen as your base to view the Kurama Fire Festival.

You can store valuables and unneeded items in lockers and carry only the bare essentials while enjoying the festival.

In addition to the baths, you can use the rest area, so if you get tired of walking, you can take your time and refresh at Kurama Onsen.

Naturally, the tour includes a meal—in particular, Kurama Onsen’s prized hitori-nabe gozen (individual hot-pot set meal).

A Wide Range of MK Travel Tours

In addition to the Kurama Fire Festival, MK Travel offers a diverse array of tours.

Particularly popular are various day trips that take advantage of the mobility of taxis, as well as pilgrimage-focused tours such as the Saigoku Pilgrimage.